350 Miles in the Arctic Refuge and a Tour of the Sadlerochits

In the early months of the pandemic Luc Mehl and Sarah Histand, and I undertook a 21-day traverse in the Brooks Range that avoided plane travel and communities. The original version was published in 23 installments on Instagram between July 19 and August 18, 2020.

Words and photos by Will Koeppen

The early months of the COVID-19 pandemic were an interesting time for everyone, especially in rural Alaska. With the absence of information, deaths spiking, and vaccinations still a year out, many Alaska villages (and their airports) promptly shut themselves off to outsiders. Backcountry trips that had been months in the planning were canceled, 14-day quarantines were mandated, and bush pilots who make their living shuttling people and goods into the wilderness suddenly faced a lot of uncertainty.

I wasn't sure what the summer was going to look like, but I was flexible. And when my friend, Luc Mehl, proposed that I join him and his partner, Sarah Histand, on a 21-day, 350-mile backcountry trip in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge that wouldn't pass through any villages, I didn't hesitate. We left a few weeks later, driving to Coyote Air in Coldfoot with the food we were sending on ahead, and then on to Deadhorse where we dropped a car, then back to Pump Station 3 on the Dalton Highway with a friend's vehicle. On the drive we saw some caribou, a shedding muskox, and a young, blond, and very fluffy bear rooting around near the road. I wished we hadn't seen the bear less than five miles from our entry point.

Pump Station 3 to the Ivishak

We walked onto the tundra at 9:30 pm on June 15, 2020. The bugs were bad, but we were happy to be out of the car. A thunderstorm loomed over the mountains in the east, and we pushed as far into it as we dared before camping on a small hillock overlooking the confluence of Accomplishment Creek and the Sagavanirktok River.

We only had one packraft between the three of us, so it took a little planning and practice to shuttle ourselves to the other side of the Sag. We jumped on a patch of aufeis in Accomplishment creek valley, which made for easy walking, fewer mosquitoes, and cooler temperatures under the high sun. A group of caribou had the same idea and kept out ahead of us. The aufeis ended, and the valley turned into meadows of willow and lupine in full bloom. It was my first long trip with Luc and Sarah, and I always overanalyze new situations like that. I worried about lagging behind, having the same objectives, or even being able to keep up my end of conversations. But it was clear after the first few hours that those would not be issues with us.

A terminal moraine swept us up and into the pass we wanted towards the Ribdon Valley. There was a lot of bear scat in the pass, but there was also flowing water and a nice breeze so we set up camp. As we ate dinner, the group of caribou we had followed all day came to visit. They nearly walked past us, but spooked a little at the last second and made their way up to the eastern ridgeline to go around.

We shuffled and slid down the steep slope from the pass to Elusive Lake. Today, the lake doesn't seem very elusive as it's only 12 miles from the Dalton Highway. But it was named by USGS geologists in 1951, and it was a historical landmark on older geology maps of the North Slope long before the road was constructed. The lake was mostly frozen over, but we thought we saw a few fish surfacing so Luc tried out his Ronco Pocket Fisherman. Whatever fish were there didn't care about his spinner.

The walking on the Ribdon aufeis was grand, and we spent some time messing around with the giant, columnar crystals of overflow and jumping on thin overhangs. We found an ultra blue section of candle ice and probed it with our hiking poles, finding out that it's really just very thin ice saturated with water.

We took a “shortcut” to the next section of the Ribdon, and had deja vu to our respective 2017 trips, when the water of the Ribdon suddenly all but disappeared. After being so wet and crossing so many stream channels, the dry channels felt eerie. After some discussion, and since I had already been to the upper Ribdon Valley, we explored Lupine Valley, a detour to the north. Soon after we turned into it we found some pieces of an old rocket from the Poker Flats missile range. Luc recalled that he had heard about this type of thing from his friend, Brad Meiklejohn, who had also provided the seductive rumor that if you find the remains of a rocket in the Brooks Range that hasn't been found before, some agency would give you a reward. It turns out that's true, and the research range is hoping to retrieve these pieces in 2024. Further into Lupine Valley, we camped at one of the best locations of the entire trip, a tundra-covered ridge overlooking a breezy, alpine lake. We all swam and dried in the sun. I proposed moving there permanently.

We didn't normally carry much water (water is very available), but Lupine Valley was an exception. It had beautiful walking. But it was hot — almost arid — with large, dry streambeds filled with fossilized corals.

The few small streams that came out of the northern side of the valley were murky and either white-green or deep red in color. Luc and I both have geology degrees, and I had seen very similar streams in Pennsylvania in college studying acid rock drainage. In brief, if groundwater passes through rock or soil containing metal sulfides it can increase in acidity until it dissolves the metals. When that water hits more neutral water like a small surface stream, it dumps out metal-ion precipitates such as iron or aluminum hydroxide. It made for dramatically red to yellow streams with thick muds that formed travertine-like ledges. Some scientists think this is related to climate change and melting permafrost. The end result was that we didn't really feel like drinking from those streams, so we had to carry more water taken from the sparse and intermittent streams on the south face of the valley.

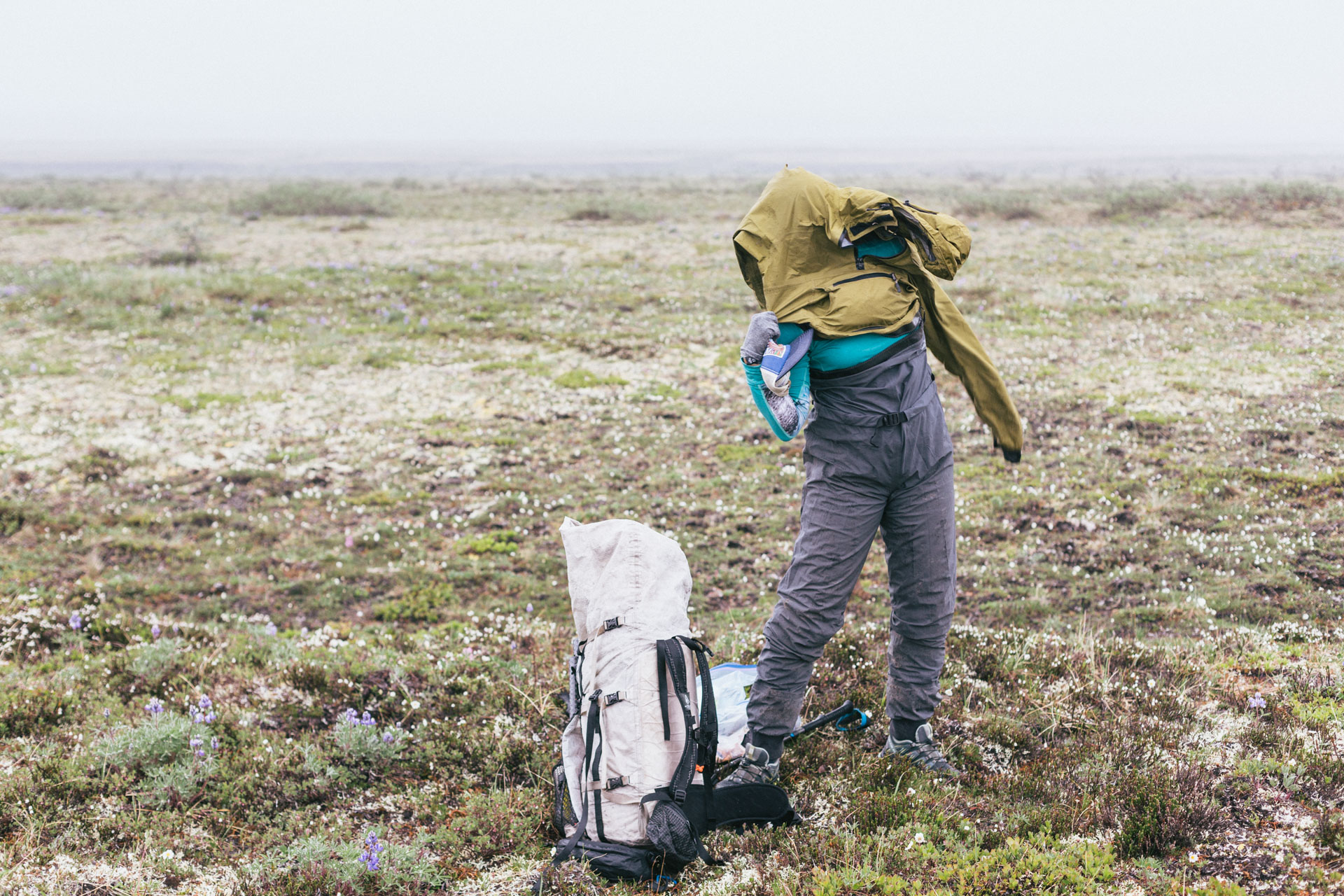

After ~13 miles we left Lupine Valley and crossed back into the Ribdon Valley. The clouds had finally caught up with us and it was a slow morning listening to rain on the tents. When it ebbed a little, we packed our gear and followed a tributary to a pass to the south. I enjoyed comparing our rain gear: Luc in his Patagonia waders and crappy rain jacket, me in an expensive rain jacket and ripped up rain pants, and Sarah in her drysuit.

The walking was easy. The low clouds and the rain kept us moving quickly to keep warm, but we still stopped to examine the variety of fossilized corals in stream. The rain rehydrated the antler and finger lichens making the tundra springy to walk on, and we followed some perennial bear tracks through the springy tundra to the lee of a large boulder to eat lunch. (Apparently bears tend to walk in the footprints of other bears near marking areas leaving semi-permanent depressions in the tundra.) As we ate, an unseen bird living underneath the boulder thrummed its annoyance.

We also stopped at a rock arch that Luc and Sarah remembered from their previous trip, though this time there was a stream underneath it. At the end of the valley were two rust-colored streams, and we climbed the steep hill between them, which kept rising and rising until it was a mountain. Luc took a compass bearing from our topo map, and we navigated through a mess of shaley ridges, soft snowfields, swampy and thin tundra, and confusing topo lines in the summit region. Over the pass, we emerged from the clouds and descended into an isolated valley — a small but majestic place with a narrow and snowy river valley upstream, a canyon downstream, and cliffs on both sides. We camped on an island and talked about how lucky we felt to be there.

Remembering that it was solstice, we celebrated by exploring the valley without our packs. I stalked a regal-looking plover and sketched some of the stacked, sedimentary layers in my journal.

Refreshed, we climbed up to a ridgeline where Luc and Sarah knew to look for an improbable game trail along the long, eastern-trending ridge. It was a beautiful line.

A few miles later we dropped into a stream that all of us had hiked in 2017. Back in familiar territory, we talked about some specific memories we had of our trips, and I thought about the nature of memory in general. It's funny what moments become anchored in our brain forever and what gets lost. We saw signs of bear, caribou, and wolf, all in the same small puddle, and another red-colored stream came in from the right. Suddenly we were back at the Ivishak River and the sky was completely clear.

We spotted our gear drop from about a mile away and it already looked heavy: three stacked plywood boxes filled with food and two duffel bags of packrafting gear on a wide open plain. We transported our cache to the river, washed, and made a fire on the gravel bar with some dead willows and the boxes that we no longer needed. We ate our “heavy meal” — toasted BLTs with fresh bread and green salads. I was impressed that all of it survived five days in the heat. We were stuffed, and the willow fluff was blowing like snow. It was so light out when we got into our white, translucent tents that Luc yelled, “sunglasses to bed!”

Ivishak to Ignek

It was hot while we packed the gear inside of the boats. But then we pushed into the Ivishak River and … ground to a halt. The water was just too shallow for us plus our gear. So we “walked the dog”, letting the river carry our rafts and gear as we followed behind holding a leash. By the time we were able to float consistently there was a strong tail wind through the winding channels that kept the heat down, and the mountains flew by. A fast 12 miles later we reached our takeout opposite a fantasy spire bowl that I promised myself I'd come back to climb.

We re-organized ourselves into backpack mode. The packs were jammed full, and we were each now carrying our camping gear, rafting gear, and 16 days of food. Plodding up the streambed was slow and intense, but Luc and I made comments like, “OK, this doesn't feel totally crazy,” — part honest assessment and part trying to convince ourselves.

After much discussion, we had decided on a low route past Porcupine Lake. In the planning stages of the trip, Luc and I had noted that this section looked very green in the satellite imagery — often a sign of backcountry suffering through vegetation and tussocks. The signs were not wrong. It was drizzling by the time we exited a narrow gap that was thick with willows into the green and tussocky expanse around the lake. At least the tussocks were young, and they grew on a shallow shale layer that didn't allow them to get too deep. It was a trudge, and I tried to do math problems in my head to pass the time. Math problems like adding up all the weight in my pack, which I estimated a few dozen different ways (82 lbs). I also picked up a mental tic that would last the rest of the trip: a strange five-chord progression that would play on infinite repeat in my head whenever there was a monotonous rhythm to be had, like walking or paddling. We took a snack break huddling in a cut bank of a shallow stream as the rain grew more steady.

Having Luc and Sarah as trip partners is a bit like wearing Zaphod Beeblebrox's sunglasses. They both have an unshakeable ability to become more and more positive as the outdoor conditions become worse. As we walked, we looked for bird's nests, poked at permafrost cracks, chatted and laughed, and dropped our packs to walk through icy, knee-deep sludge to play in a beautiful set of aufeis landforms. Another excellent game trail, the width of a human foot and filled with the most wolf tracks and scat any of us had ever seen in one area, took us straight down the valley. After a 12+ mile day with the heavy packs, we set up camp. A few hours later it really started to downpour. The temperatures dropped, and then, in the words of my inReach weather report, it turned into a “heavy wintery mix.”

Predictably, we were slow to get out of bed the next morning. There was only about an inch of snow on the ground. Much more than that had fallen, but it was melting quickly. When the sky cleared up a little, Luc and Sarah started a morning banter (which was typically my cue that things were happening), and we all popped out of our tents. The sun even broke through for a moment.

Back into boats, we floated, dragged, and walked the dog down the tributary. It was still pretty shallow, but I was much happier having my gear carry me than the other way around. A few miles later we merged into the Marsh Fork, which in contrast seemed to be at flood stage after the long day of rain. It was fast, muddy, and there were uprooted willows sailing past.

The water was choppy and splashy with sizable wave trains to avoid. A solid headwind with rain soon became driving ice crystals — we called it "non-ideal weather." I was warmer in the raft with its sprayskirt, and during our out-of-boat snack breaks Luc used his PFD whistle to lead exercises that we all followed without question: high stepping, grapevines, or dancing in place on the river's banks to stay warm. Finally we called it, set up tents on a gravel bank among some willows for shelter against the wind, peeled off wet clothes, and ate dinner in our sleeping bags.

The sun came out in force as we left camp, and it was a welcome sight. We navigated the braided channels of the delta where the Marsh Fork meets the Canning River, and the rest of the day was spent in discussion with the wind and trying to stay in the main channel. The Canning River sees a fair amount of rafting-related tourism, and for the first and last time in the trip we saw two other groups of humans. We floated close to 22 miles, a pretty good day, when suddenly the wind died out completely. It felt bad to stop when conditions were so nice, so we paddled another 13 miles with the northern sun sparkling off the river.

We pulled over on a gravel island by a small waterfall. Luc and Sarah got out of their boats to look for any areas of fine gravel that would be good for our tents. I was last into port, and I couldn't keep my eyes off a big brown boulder across the river. "Bear rocks" (rocks that look like bears from a distance) are a common sight in the backcountry, but it still feels silly when you're the one to call attention to an inanimate object. I mentioned it to Luc anyway, who looked at it and then passed it on to Sarah. They kept scouting for campsites, but now added some occasional hollering and sidelong glances at the boulder. Then it stood up. A muskox! It trundled off through a small copse of willows, and Sarah collected qiviut from the nearby stand of trees. We ate freeze-dried raspberry crumble around a fire until the rain clouds that had been building in the mountains opened up.

In the morning, we pushed our boats back into the fast-moving train that is the Canning River but pulled over almost immediately to watch a herd of muskox, counting at least ten adults and two calves. Then we began to fly. The main channel of the Canning River is speedy — almost 7 mph without padding — and we quickly made time to Ignek Creek, dumping our gear out on the lupine-covered river banks. We decided to take six full days of food into the Sadlerochits, leaving a cache of our rafting gear and six more days of food in bear bags by the river.

Le Tour de Sadlerochits

Ignek Valley was wide and flat, and the water of Ignek Creek stained everything red. It was hot, and even late in the day we felt like we were always trying to cool down. We saw another large brown shape that we hoped was a muskox, but it turned out to be a bear after all. It stood up to look at us, curious, and then it continued rooting around downstream while we continued up. We found interesting geology near Red Hill: an abundance of marine fossils in the creek bed; the hill itself, which appeared to be shale with indiscernible bedding planes; and a foot-thick rock layer with a bulbous morphology that gave the impression of flowing down the slope of the cutbank — a sandstone turbidite.

We climbed and camped on a foothill at the edge of the mountains that had a commanding view of the valley. There was an old cairn there, and the next morning we found some old, steel fuel containers and beer cans — Carling Black Label Red, with a label design from the 1950s.

We climbed through a small notch and ascended to the limestone ridge behind our campsite. Later, we read that it was called the Wahoo Limestone, and it was the perfect ramp into the Sadlerochit Mountains. The layers were filled with crinoid fossils, and Sarah found two pieces of what I think are the aboral cup (or possibly the holdfast). I spent my entire undergraduate geology career looking for non-column parts of crinoid flowers, so I was more than a little jealous.

Ignek Valley is bounded on its north side by a semi-continuous, nearly 9-mile-long ridge of tilted layers. It's very distinctive with black, orange, and red rocks, cliffy on its steep side and a very consistent slope on its valleyside. From the satellite imagery, Luc thought the ridgeline might be gravel, perhaps even bikeable on a future trip. We climbed a steep talus slope to gain the ridge, excited for some easy walking. It turned out that it was not bikeable. The ridge, and the entire valleyside slope, was talus — big polygonal plates of sandstone, most of which teetered and clanked as we walked on them. Luc made fun of himself too much for Sarah and I to really chip in much.

We walked slower than expected but admired the outstanding views of the Shubliks to the south, even as we looked longingly at some tempting circuits through the smoother mountains to the north. A large cairn balanced on the ridge peak, and we found more fuel and beer cans and an old packboard. This was no place for hunters, but rather a ridge that only a beer-drinking geologist could love. After the trip, I read about a few such mapping parties, all looking to determine prospects for oil in the region. It surprised me that they left trash, but it all took place ~75 years ago, in a different era. We used snow patches when possible, following the ups and downs of the undulating ridgeline. The camping situation seemed to be a choice between sharp rocks or wet tussocks, but then we found a limestone saddle with "1 ½ spots". I used extra clothes beneath my sleeping pad to flatten out my tent spot.

The next day we started around noon, after sleeping in and reading in the sun. Maybe there was also a little reluctance since we knew we were going to be walking another five miles of the talus ridge. But walk it we did. There were no cairns or other signs of our intrepid historical geologists, but the weather was beautifully clear, and we could see the sea ice in Camden Bay 30 miles away. Still, by the last mile or so, we were all ready to be done with talus.

We took a break near the end of the ridge and had a long discussion about where our feet should take us. With four days of food in our packs we considered two options. Option A (60 miles) was a longer route across the foot of the Sadlerochits cutting south through the range near Mount Weller. Looking across the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge gave us the possibility of seeing caribou herds, and we had heard from a pilot that Mount Weller was an interesting area. On the other hand, we'd have to come back through Ignek Valley, territory we had just looked at for three days. This option also meant 15-mile days and had the possibility of a sketchy ascent over an unknown limestone headwall. Option B (45 miles) was to move more leisurely south through the Shublik mountains. This would allow us to keep doing shorter, 10-12 mile days and not repeat any terrain.

Nearing the end of our third day of hiking less than 10 miles, Luc and Sarah felt ready to crank. I was a little worried that, depending on the condition of the Kavik River to Deadhorse, the whole rest of the trip might turn into a crank. But I was also prepared to get on my giddy-up. As Luc pointed out, our packs would never be lighter while we weren't carrying the rafts. Together, we decided to walk the Katakturuk Valley north out to the coastal plain, camp, and decide in the morning. In the tent, I revisited my trip goals, and I was ready to say yes to the longest route, even though I preferred the relaxed option. At 8:15 am we conferred, and Luc said, “Sarah is interested in the whole banana.” (“Not my words!” she said later.) Option Whole Banana combined the Mount Weller entry with a return through the Shubliks via an “easy” pass — the catch being that it was a long route, and required committing to four 16-mile days. Let's go.

The northern face of the Sadlerochits look long over the coastal plain to the Arctic Ocean. It's green, filled with flowers, and immensely beautiful. But it's also kind of monotonous terrain with ankle-grabbing swamp and tussocks occasionally punctuated by low hills. It's the kind of hiking where five-chord progressions reign supreme. I was absorbed in my own thoughts when Luc abruptly asked, “Is that an animal or a pile of dirt?” We gave a yell, and the pile of brown turned a big head towards us. It was a good-sized bear, about ~150 ft away, lying on its back and comically spread-eagled in the sun. Its body didn't move, and the head rotated sleepily away. We backed up and prepared to circle around and get upwind. Suddenly the bear jumped up eyeing us and, after a half-minute of consideration, it bolted, running directly up the side of the mountain it had been sleeping under.

We climbed back into foothills and then mountains, and we found a caribou superhighway — trails and trails and trails, as if tens to hundreds of caribou walked shoulder to shoulder contouring east. Backcountry walking is often filled with unknowns, so finding and following these trustworthy signs of mass migration gave us a big morale boost. We walked in their tracks up and down valleys and across the cobbly Nularvik River. We stopped to swim in a waterfall among the castles and caves of East Nularvik Creek, and in the pass below Mount Weller we found two caribou lazily munching away. We had hoped to camp there, but it turned out to be a cold, windy, and rocky place. After the long day we felt like we really deserved a great spot, so we made it even longer by walking a few additional miles to an elevated bench above Camp 263 Creek. We ate in exhausted but blissed out silence.

The problem with having really great conditions for walking is that those sections seem to go by too fast. We left the clear water and gravel stream beds of Camp 263 Creek to hike through a swampy pass into the wide valley that separates the Sadlerochit Mountains from the Shubliks. We talked a little, wondering if the cotton grass bloom might be visible from satellite imagery, or if radar could be used to map out the surface roughness of tussocks. We stayed high on the flanks of the valley and worked our way back west for as long as we could before diving into the flowers. Even though we still had a week left, there was a change to be felt. We were no longer going out, we were coming back in. We saw more bears: a sow and its three cubs running and tumbling behind her.

The eponymous Sadlerochit River was nearly opaque with black silt. Walking upstream we found the source, a cut bank where the river was eroding some dark, finely-bedded unconsolidated material. The mud near the cut bank settled in thick, glistening pools with strange half-fluid, half-solid properties.

We turned up Fire Creek, a name given to it by USGS geologists in 1948 because it flows partly through Ignek Valley, and ignek — or “iqnik” according to more modern language sources — means “fire” in Iñupiaq. It's an apt name because it's filled with red and orange pool-drop waterfalls zigzagging through exposed geologic layers.

As we walked, Luc watched the river constantly, and he started to really agitate for a swim over one of the drops. I thought he was out of his mind. Mostly because Fire Creek was home to more mosquitoes than any other place I've been to on Earth. (I rarely use bug spray on backcountry trips, preferring to keep covered and/or moving, and I almost never use a headnet. That changed in Fire Creek.) Luc was determined though, and he took one run over a small drop and then cheered so loudly that he convinced Sarah to take another, as I saw the mosquitos try to carry away their clothes.

We woke up in a cloud, and it was gusting heavily with light but horizontal mixed rain and snow. We wouldn't take off our rain gear for the rest of the day. I tried not to notice the sunlight filtering down to the valley a few miles behind us as I rolled on my cold, wet socks. More than once I asked Luc about his hiking waders, hoping to live vicariously through his dry socks encased in rubber booties, but he said his feet were too numb to tell if they were wet or dry anyway.

Given the low visibility we were grateful that the pass above Fire Creek was a mellow climb, but it was also soggy with saturated snow patches and pelting ice and rain. On the other side, we quickly dropped out of the mist to get back our visibility, but it was still windy and rainy, the kind of day where you walk fast to stay warm. We descended by traversing slopes of slippery talus to stay out of the canyons below until the valley widened and we could start following gravel bars again. Into and quickly out of Ikiakpaurak Valley overlooking Cache Creek, we used a series of low, tilted hills as a ramp back north into the mountains. Six hours after we started, as the rain stopped and we poured on the miles, I started to feel warm. The tributary we followed was filled with canyon-making limestones of all sorts, and we stopped to poke around at the rugose corals and the pounding, 20-ft waterfalls created as Nanook Creek plunged through geologic time.

The sun came out the next day but the mosquitos never did, tamped down by the sleet the day before. Nanook Creek was a gradient of colors with aquamarine water (sometimes clouded white) in red and white-stained channels. The rocks were thick with fossils and narrow, water-carved drops.

Re-entering Ignek Valley, we passed a historic tent circle on one of the rocky terraces. It would have been a great hunting spot, located at a wildlife funnel into and out of the Shubliks. Then we cruised on the smooth and dry terrain, stopping to check out a wolf skull and watch a moose lope across the flank of the mountains. A caribou came over, rather close. Someone said they don't have good eyesight, but Burch, 1972 writes: “Caribou eyesight is good in that animals can see objects at some distance, but they do not differentiate readily between dangerous objects and harmless ones.” He goes on to say that he thinks caribou are really just very curious creatures. We'd see that time and time again. Our cache at the Canning River was untouched, and we did a full gear dry out in the sun. It was an early night, but by the next day we'd need all the sleep we could get.

Kavik Creek to Deadhorse

We paddled across the Canning River and made our way to the Kavik. Leaving the Canning also meant leaving the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and it immediately coincided with finding the detritus of human industrial activity in pursuit of oil. It felt pretty weird, being as remote as we still were, to roll up on a pile of fuel barrels or the remains of a support structure. It was even weirder to walk across or along the straight lines dotted by damaged permafrost that run for miles into the distance — permanent scars in the landscape where people drove heavy vehicles conducting seismic surveys nearly 60 years ago.

The crossing had just one large, rounded ridge to go over, but it was almost entirely covered by deep cotton grass tussocks. As we had expected, they were hard miles, but I appreciated our trio's positivity — my favorite trip partners can talk about the difficulty of a section without letting it impact our joy of being outside in a new place with friends. Sometimes we found threads to follow: a set of tire tracks that subtly muted the vegetation; a drainage that had a bit of snow and gravel in it; even the marshy ground, where it seemed to be too wet for the cottongrass to take hold, was easier than walking in the tussocks. Luc put in headphones and listened to music for a break. Sarah and I talked about mental techniques for getting through emotionally hard times. It took us ~7 hours to make the 10 miles.

Seeing the Kavik was a sight for sore eyes but also a reckoning. I had spent the last week or so making jokes about hoping to be able to float the Kavik River, psyching myself up in case we had to walk the 60 miles to the coast. So, I was totally relieved when there was water, and it was moving. Luc, who had higher expectations for the flow, was less pleased, and he suggested we float “a few easy miles” to see the character of the river. We put in our boats around 9 pm. It ended up being a beautiful night, and with a tailwind that felt like ice when we stopped, we just kept going and going. Through many shallow riffles and sweeping and diverging channels, through willows and along shaley bluffs. We finally pulled over at 3 am, after nearly 20 miles on the water.

Daytime hours brought cold headwinds blowing off the Arctic Ocean, and we quickly came to the conclusion that it was going to be pretty futile to paddle the slow water of the Kavik against even a light breeze. So we flipped our schedule, resting during the day and paddling overnight. After our days of making miles, it was hard to stop and wait. I read my book, slept, and tried not to eat all my day snacks in one go. The sunny side of the tent would bake, but shady side was chilly.

Every day, like magic, the wind died down at 9 pm, and we paddled out. Out of the foothills of the Brooks Range, the Kavik River is sometimes like a slow stream and oftentimes like a series of connected lakes. Most sources say that 2-3 mph is an average speed for paddling on flat water, and the Kavik certainly didn't add much more. It was cold and humid in the low-angle light. We wore our puffy jackets inside our drysuits and used gallon ziploc bags as makeshift pogies to protect our hands.

It was slow, but also incredibly beautiful. In the late evening, a dense fog drifted across the river obscuring the sun, then it drifted away. Flocks of geese honked overhead, ducks of all kinds took off from crystalline side channels. From midnight to 2 am a thin steam rose off the river and its icy banks, and the water nearly merged with the sky. We skirted a large piece of permafrost dangling from the 15-foot high bank. It was hanging on by a few roots. Two minutes later we heard a crash, looked back, and it had fallen. The air started to smell like salt and fish.

Staying up all night can make you feel amazingly drunk, and my mind drifted in and out of active consciousness. But after three nights of paddling I found that I appreciated seeing the bottom vertex of the sun's parabola and its effects on the animals and landscape, and I was surprised that we could tell the difference between midnight and 1 am by the slightly warmer feeling of the sun on our faces.

Within a few miles of the ocean, now on the Shaviovik River, the channel widened significantly and became very shallow, often a foot deep or less. We tried to choose channels with the most water, and sometimes it seemed like we chose wrong, but there was nowhere to go but forward. Sarah spotted a few caribou on the shore, and then more and more appeared on the river bluff. We pulled over to watch them cross the river. A large group seemed to pile up until some of the largest caribou finally just went for it, wading through the river. The others followed, and soon the entire bluff was a slow conveyor belt, moving all the rest of the caribou up to that position to cross. We saw at least 500 animals, but being at water level, below the river bluff, we never got a full view of the herd. A mile later we floated past a feeder pipeline moving oil towards Deadhorse.

In the Shaviovik Delta I had a hard time keeping my bearings. There was little to no flow on the river, the banks were low and drifted in and out of the fog, and the sky was immense as we paddled directly towards the sun. Thick clouds over the Arctic Ocean and the moonlike landscape gave me the impression of being able to see the planetary curvature, and I got a little vertigo, feeling like we were sliding forward off the end of the Earth. In the fog we came upon a caribou acting distraught, running back and forth over a bundle on the shore — it was a calf, probably drowned. I couldn't bring myself to take a picture.

The last mile to the coast was the longest. The water in the delta was inches deep, and we scouted and scooted our way forward, paddling against the open ocean wind. We camped on the Beaufort Sea coast, in the lee of a bluff as low surface clouds poured in. A caribou looked at us like the aliens we were.

Walking west, we followed the coastline of aptly named Foggy Bay. The thin gravel beach was strewn with caribou tracks, driftwood, and quite a bit of trash: the ubiquitous fuel barrels, construction debris, styrofoam of all shapes, purple nitrile gloves, a plastic coffee mug with a broken handle. The beach was a little soft to be called perfect walking, but none of us were complaining.

Where the Kadleroshilik River enters the ocean, it makes a small delta and island system. The sun came out and the wind was at our backs, so we inflated our boats and paddled to the islands. It was pretty dreamy, walking the thin strip of sand between a sparkling lagoon and the ocean crowded with sea ice. Flocks of snow geese herded their flightless chicks away, hopping from berg to berg. The remnants of a sturdy little cabin had just enough space for a stove, bathroom, and sleeping bench. Nearby, next to a rusty fuel barrel staked like a scarecrow on a metal pole, a group of eider nests each contained a few pale green eggs. The second half of the delta crossing had no islands, so we wiggled through the icebergs in our boats. Returning to the continent we found an old camp with a few plywood structures and a pile of rusty bed frames.

We had to weave around some inlets and swamps, and on one of these diversions I slipped and fell back into the black, oily mud. With the pack on, I had to roll over to get up, planting my hands a foot deep into the soft mud. They came out smelling like diesel fuel.

A blustery wind picked up as we turned south, walking up the Sagavanirktok River. We hopped between the bluffs and the dry, textured channels of the eastern delta. The latter reminded me of being in a Mad Max movie.

A friend of Sarah's worked in Deadhorse, and she asked him about traversing the Sag delta. His response: “Sarah, I know you're an adventurer, but have you ever walked through muskeg?” The USGS map shows the North Slope as being completely marshland. Thankfully that is not accurate. It's a mix of swamp, lakes, and a surprising amount of walking that is just slightly damp. In short, it wasn't that bad, at least not in July. Turning west, we crossed the many forks of the river, keeping the oil infrastructure on the coast in view on the horizon. The section between the east and main forks of the river was just a little thick with knee-deep marshes, but if your foot pushed down far enough you could feel the supportive permafrost below.

We inflated the boats one last time, paddling down the westernmost river channel northward to the edge of Deadhorse. And then we walked the road the last 1 ½ miles to Sarah's car and hugged each other in the gravel parking lot of Delta Leasing. It was a strange endcap after spending 21 days in the backcountry to cross 344 miles in the Arctic Refuge. And maybe it always is.